Author: Site Editor Publish Time: 2025-07-22 Origin: Site

Fast medium-wave infrared (FMWIR) lamps have become a core technology in modern industrial heating. They deliver rapid response, high power density, and precise temperature control, making them well suited to processes such as drying coatings, thermoforming plastics, glass processing, and food drying.

This guide is written for process engineers, plant managers, and equipment designers who need to specify, justify, and maintain infrared (IR) lamp systems. It explains how to choose and apply fast medium-wave lamps in a way that is technically sound, safe, and cost-effective.

Industrial infrared heating typically uses three main spectral bands.

Short-wave (near IR)

Approx. 0.7–2 μm

Very high emitter temperatures (often above 1,800 °C)

Deep penetration in some materials, intense heating, high visible light

Medium-wave

Approx. 2–4 μm (sometimes extended to about 5 μm in practice)

Moderate emitter temperatures

Strong absorption by many plastics, glass, water, and organic coatings

Long-wave (far IR)

Approx. 4–15 μm and beyond

Lower temperatures, ceramic or alloy elements

Gentle surface heating, comfort and low-temperature drying applications

Fast medium-wave lamps sit between traditional short- and medium-wave solutions. They typically use a quartz envelope and a tungsten or similar filament operated at elevated temperature, giving:

Peak output roughly in the 1.4–2.5 μm region

Medium-wave-dominant spectrum with a strong near-IR component

Very low thermal inertia: full output in a few seconds or less

This spectral position is especially efficient for thin materials and surface layers containing water or organic compounds, such as coatings, inks, and adhesives, because their absorption peaks sit in the mid-infrared.

Infrared heating is essentially radiative heat transfer. Efficiency is maximised when:

The lamp’s emission spectrum overlaps the material’s absorption spectrum, and

The geometry allows a high view factor between emitter and target.

If the wavelength is poorly matched, much of the radiant energy is reflected or passes through without being absorbed, forcing longer cycles and higher power input. When properly matched, infrared heating can significantly reduce drying time and energy consumption compared with convection-only systems.

Fast medium-wave is not a universal answer. It is most effective when several conditions are present.

Surface-dominated heating

Thin films, coatings, textile webs, paper, films, and sheets where heat only needs to penetrate a few hundred microns or millimetres.

Moderate process temperatures

Typical product or surface temperatures in the range of 50–500 °C, common in drying, curing, and thermoforming processes.

Frequent start/stop or rapid recipe changes

Lines with intermittent production, multiple product formats, or zones that must ramp quickly and shut down between batches benefit from fast response and low thermal inertia.

Energy-efficiency constraints

Facilities under pressure to reduce energy use or emissions can leverage high electrical-to-radiant conversion and the ability to heat product directly rather than the surrounding air.

Limited installation space

Compact heaters with focused radiation and integrated reflectors can deliver high power densities in constrained ovens or retrofits.

When deeper bulk heating of thick metal sections is required, short-wave or other technologies such as induction, combustion, or dielectric heating may be more appropriate. Conversely, for low-temperature comfort or building heating, long-wave emitters are usually preferred.

A rigorous selection starts with the material’s absorption characteristics. The following ranges are typical engineering guidelines.

Water and water-based coatings

Strong absorption near 2.7–3.0 μm

Fast medium-wave is highly efficient for drying waterborne paints, inks, and food products.

Many plastics

Multiple absorption bands between 2–4 μm, often strongest around 2.5–3.5 μm

Fast medium-wave is ideal for sheet and film preheating, thermoforming, and lamination.

Glass

Significant absorption in the 1–3 μm range

Fast medium-wave can be tuned for cutting, bending, and preheating operations.

Metals

Higher reflectivity in medium-wave; better absorption below about 1.5 μm

Short-wave IR or other methods usually perform better for direct metal heating.

Where possible, support lamp selection with absorption data, in-house tests with different emitter types, and thermal imaging during pilot runs. This evidence-based approach improves efficiency and reduces the risk of poor heating uniformity or product defects.

Sizing begins with a basic energy balance. For a batch of mass m (kg), specific heat c (kJ/kg·K), temperature rise ΔT (K), and desired heating time t (s), calculate theoretical power and then add margins for losses and control.

In practice, the installed lamp power must also cover:

Heat losses through convection, conduction, and unwanted radiation

Reflection from the product surface

Start-up transients and process variability

Design power density is often 1.5–3 times the theoretical minimum, depending on enclosure design, airflow, and insulation quality.

For continuous lines, translate the energy requirement into kilowatts per metre of line width and then derive emitter spacing and rating based on web or product speed, required residence time under infrared, and maximum allowable surface temperature. This quantitative step is critical for justifying capital expenditure and proving that energy reduction targets are realistic.

Key mechanical and optical parameters include:

Lamp type

Single-tube or twin-tube quartz designs

Straight or contoured to follow product geometry

Heated length and cold zones

The effective heated length should match the process width or specific heating zones.

Cold ends protect seals and connections from thermal stress.

Filament design

Coil pitch, shape, and distribution strongly influence power density and uniformity.

Reflector system

Integrated or external reflectors enhance directional output and reduce losses to the rear and sides.

The reflector geometry should be engineered to maximise irradiance on the product.

Careful design of lamp and reflector layout can often deliver more performance gains than simply increasing wattage.

Fast medium-wave lamps are valued for short response times—often in the range of a few seconds to reach operating power. The control system should leverage this capability with:

Phase-angle or burst-firing control for smooth power modulation

Closed-loop temperature control using pyrometers or infrared cameras

Zoned control along product flow to match local heat demand

High-speed control allows reduced overshoot, fewer thermal defects, lower standby power, and rapid adjustment for changes in line speed or product type.

Typical lifetimes for high-quality fast medium-wave lamps are in the thousands of operating hours, depending on power density, switching frequency, and environment.

To maximise reliability:

Specify lifetime conditions, including power level, switching cycles, and ambient temperature.

Control the environment by avoiding excessive vibration, airborne contamination, or mechanical shock, and by providing adequate ventilation or cooling.

Implement a cleaning and inspection regime; keep quartz envelopes clean to avoid hot spots and loss of transmission, and check reflectors for degradation or contamination.

A documented maintenance plan and spare parts strategy should be part of the initial project.

Industrial infrared equipment must comply with electrical and thermal safety principles defined in relevant international and regional standards. These frameworks address protection against electric shock and fire, over-temperature protection, guarding and access around high-temperature components, and appropriate labelling.

Typical engineering measures include:

Temperature limiters and independent safety thermostats

Mechanical guards and interlocks to prevent contact with hot surfaces and live parts

Proper earthing and cable sizing

Enclosures with appropriate protection ratings where water, dust, or cleaning fluids are present

Worker protection should consider eye exposure, skin exposure, and ergonomics when loading or unloading near infrared sources.

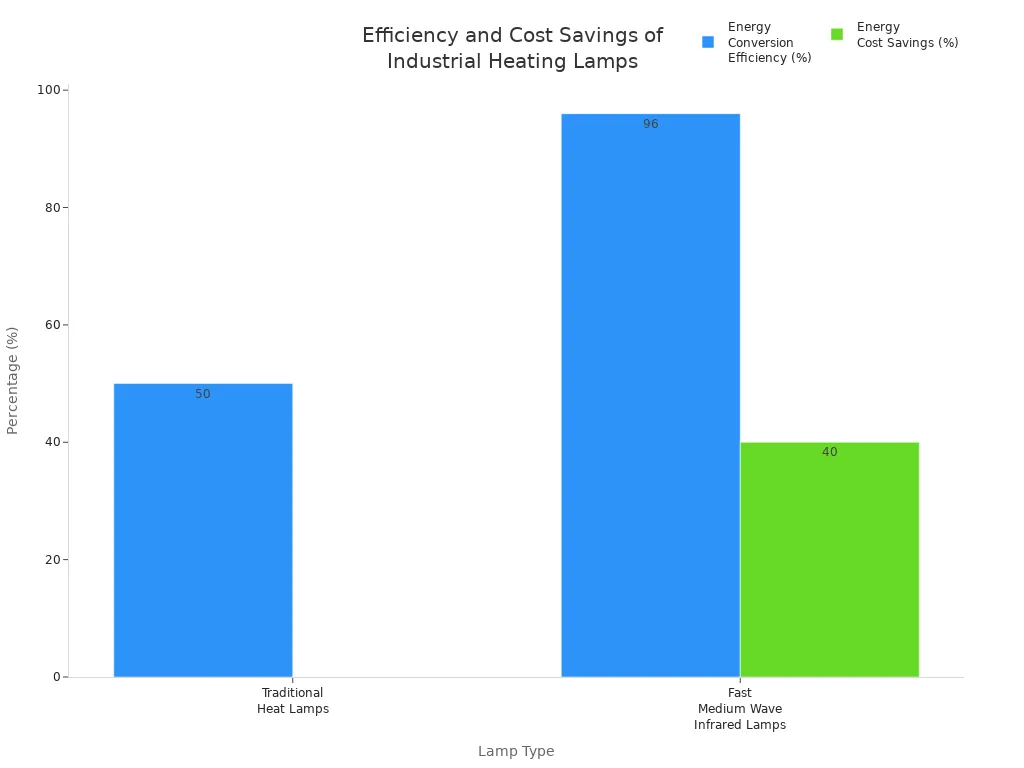

Fast medium-wave lamps may appear more expensive at the component level than simple resistance heaters, but their total cost of ownership often compares favourably because electrical-to-radiant efficiency is high, heat is applied only where and when needed, process times can be reduced, and footprint is smaller than convection ovens for the same throughput.

A robust business case should consider energy consumption before and after infrared integration, changes in scrap rate or rework, throughput gains from shorter cycles or higher line speed, and maintenance and spare parts costs over the expected life of the system.

A practical engineering approach typically follows these steps:

Define process targets

Product, material stack-up, required temperature profile, dwell time, and quality criteria.

Characterise the baseline

Measure current temperature distribution, energy use, and defects on existing equipment, if any.

Choose the spectral strategy

Confirm that fast medium-wave is appropriate given the material absorption and target temperature; consider short- or long-wave solutions for comparison.

Size and layout emitters

Determine power density, lamp length, spacing, and reflector geometry to achieve the required irradiance distribution.

Design controls and interlocks

Define temperature sensing, power control, interlocks, alarms, and integration with higher-level control systems.

Prototype and validate

Conduct pilot tests, capture temperature profiles and product quality, and refine design before full-scale deployment.

Good installation is essential for both performance and safety:

Maintain adequate clearances between emitters, products, and flammable materials.

Ensure rigid mounting to prevent vibration and misalignment.

Provide accessible adjustment points so angle and distance can be fine-tuned during commissioning.

Route cabling away from high-temperature regions and moving parts, using appropriate high-temperature insulation where needed.

Plan cooling airflow so that it stabilises component temperatures without disrupting infrared transfer to the product.

During commissioning, treat the infrared system as a controllable process rather than a fixed heater:

Use thermocouples, infrared cameras, or pyrometers to map surface temperature distributions.

Trim power in each zone to eliminate hot and cold spots while meeting target throughput.

Establish standard recipes defining power levels versus line speed and product type.

Capture baseline data for energy consumption and product quality as a reference for future optimisation.

Fast medium-wave lamps are well suited for edge heating for cutting and scoring, bending and forming of automotive or architectural glass, and preheating before tempering or lamination. The spectral match between fast medium-wave output and glass absorption allows rapid, localised heating of the surface and near-surface region. Compared with purely convective systems, infrared can shorten heating times and reduce thermal gradients that cause warping or micro-cracks.

In plastics processing, fast medium-wave lamps are widely used for heating sheets for thermoforming and vacuum forming, preheating films for stretching or lamination, and localised heating in injection or blow moulding preforms. Because many polymers absorb strongly in the 2–4 μm band, infrared energy couples efficiently into the material, allowing rapid, uniform heating and shorter cycle times. Properly designed lamp arrays and reflectors minimise edge overheating and thickness variation.

Fast medium-wave infrared is particularly effective for curing industrial coatings and primers, drying inks in printing and converting lines, and curing coatings in automotive and general industrial finishing. Radiation can penetrate the coating layer and heat the substrate from within, helping solvents or water escape more uniformly and reducing defects such as blistering, orange peel, and poor adhesion.

In food processing, infrared heating can shorten drying times, improve energy efficiency, and help preserve product colour and flavour. Fast medium-wave emitters are used for drying fruits, vegetables, grains, and herbs, roasting nuts, coffee, and snack products, and providing preheating or surface treatment as part of a broader thermal process.

Industrial projects involving fast medium-wave lamps often underperform for predictable reasons:

Ignoring wavelength and material compatibility and selecting emitters based only on power rating or cost

Under- or over-estimating required power density, sizing based only on rules of thumb without an energy balance

Neglecting reflector and geometry design, installing powerful lamps but with poor optical layout

Weak control and instrumentation, relying on simple on or off control with minimal sensing

Safety and documentation gaps, such as inadequate guarding, missing interlocks, or incomplete instructions

For a new or upgraded system, the following checklist supports a robust selection:

Material analysis

Confirm that the product and any coatings have absorption peaks compatible with medium-wave infrared.

Process definition

Define target temperatures, dwell time, throughput, quality metrics, and allowable thermal gradients.

Energy and power calculations

Complete a basic energy balance and determine design power density with allowance for losses and control margin.

Emitter selection

Specify fast medium-wave emitter type, length, and rating; ensure spectrum alignment with the material.

Optical and mechanical design

Engineer lamp arrangement and reflector system for uniform irradiance and ease of maintenance.

Controls and safety

Select a closed-loop control strategy and define interlocks, temperature limits, and emergency stops.

Validation plan

Define test methodology and acceptance criteria before commissioning.

Fast medium-wave infrared lamps are a powerful tool for industrial heating when applied with proper engineering rigour. By starting from material properties and process requirements, matching spectral output to absorption behaviour, and following established safety and control practices, engineers can design infrared systems that are efficient, controllable, and robust over their entire life cycle.