Author: Site Editor Publish Time: 2025-09-10 Origin: Site

One-sentence overview: Infrared heating, correctly specified and instrumented, lets digital printing lines run faster while protecting color, finish, and substrates; this guide explains the physics, selection, sizing, control, safety, troubleshooting, and rollout.

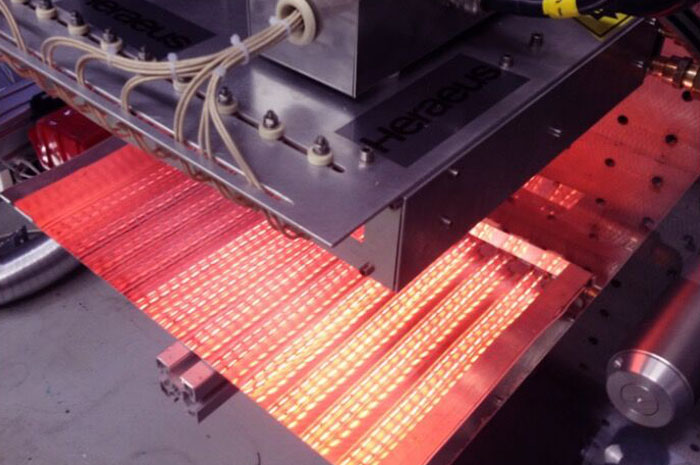

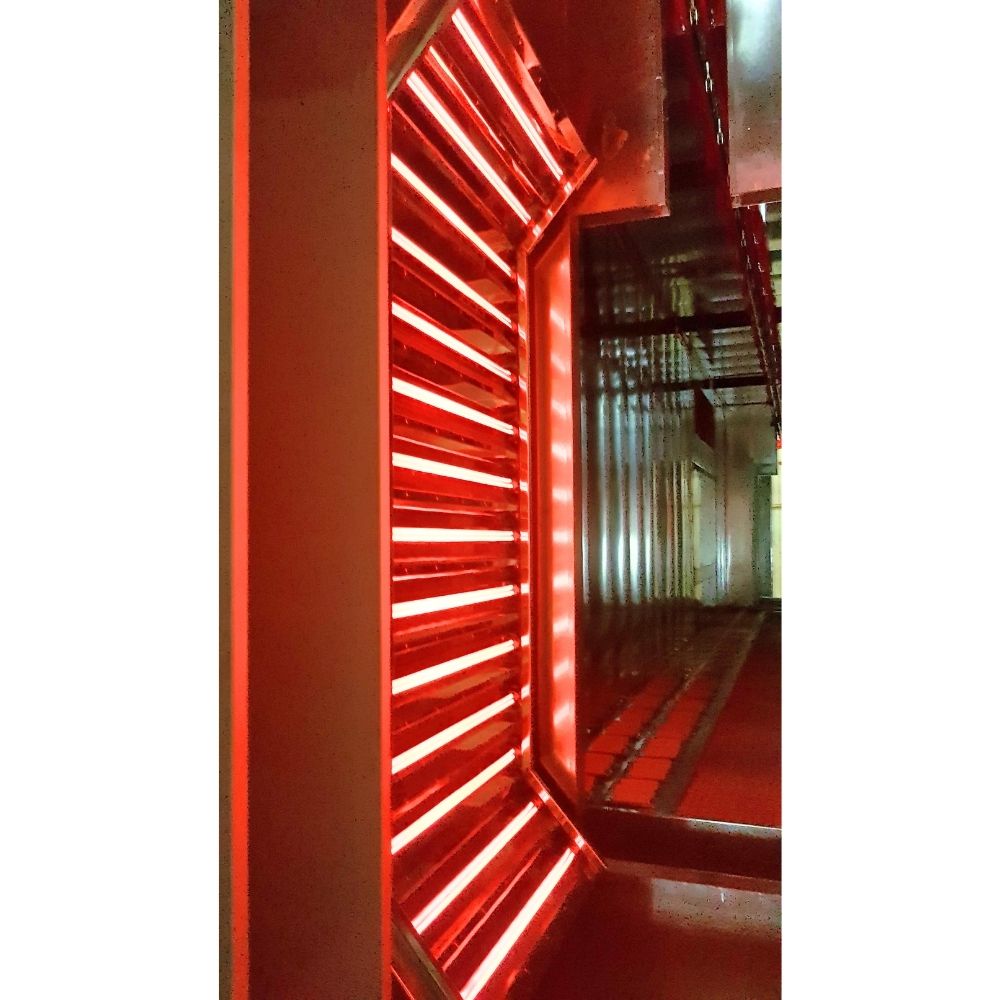

Infrared (IR) delivers radiant energy directly to inks and substrates. Unlike convection, which relies on bulk hot air, IR can raise surface temperature quickly and predictably. The benefit in digital printing is twofold: higher line speeds through faster evaporation or cure, and tighter control over the thermal history that affects dot gain, gloss, and adhesion.

Key principles you need:

Spectral match matters. Different materials absorb different IR wavelengths. Water in aqueous inks absorbs strongly in specific near- and short-IR bands; some polymers and pigments respond differently. Aligning emitter output to the dominant absorber improves efficiency.

Power density and dwell time are the levers. Drying rate depends on instantaneous irradiance (kW/m²) and the time the web spends under effective radiation.

Air movement still counts. Even with IR, vapor must be swept away; otherwise, a boundary layer slows mass transfer and can cause micro-blistering.

Quick answer — “Which wavelength is best for water-based inks?”

Medium-wave ranges, especially fast-response designs, generally couple efficiently to water while giving a forgiving process window for paper, films, and textiles.

Post-nozzle drying and cure: Evaporate water or solvent after laydown; stabilize ink before downstream handling.

Substrate pre-heat: Bring films or papers to a controlled temperature to stabilize viscosity and dot formation.

Adhesion promotion and post-cure: Support intercoat bonding and final film properties.

Dye-sublimation and textiles: Provide uniform, controllable heat to support color development without scorching.

Hybrid stations: Combine IR with directed airflow and, where relevant, UV LED for mixed chemistries or multi-step film formation.

Quick answer — “Can IR be combined with UV LED?”

Yes. Use IR to pre-set or remove liquid carriers, then let UV LED complete polymerization. Hybrids often raise speed and stabilize gloss.

| Emitter type | Response | Typical role | Strengths | Watch-outs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-wave quartz | Very fast | High-speed lines with tight space | Instant control, compact footprint | Surface-biased heating; overshoot risk on thin films |

| Fast-response medium-wave (incl. carbon) | Fast | Aqueous systems, general web | Efficient coupling to water; balanced penetration | Requires adequate airflow to clear vapor |

| Medium-wave quartz | Moderate | Coated papers, textiles | Even heating, good for moderate speeds | Larger modules; more dwell needed |

| Long-wave ceramic | Slow | Gentle pre-heat, post-cure | Substrate-friendly, uniform | Not ideal for very high speeds |

Selection rules of thumb

Match the emitter spectrum to the absorber (ink vehicle, substrate).

Start with the fastest response your process can justify; faster response simplifies control.

For sensitive films, prefer wavelengths and power densities that heat evenly at moderate surface temperatures.

Drying has two energy components: phase change (vaporizing liquid) and sensible heating (raising temperatures of ink, substrate, fixtures, and air).

Baseline formula (per second):

Required power ≈ (volatile mass flow) × (latent heat) × (safety factor) + (sensible loads)

For water near 100 °C, latent heat ≈ 2,256–2,257 kJ/kg (use 2,256.7 for quick math).

A reasonable initial safety factor is 1.2–1.4 to cover inefficiencies and ramping.

Sensible loads vary; start with 10–30% of the phase-change power if you lack measurements.

How to compute volatile mass flow

Convert line speed to meters per second.

Multiply web width by speed to get area per second.

Multiply by coat weight of volatile (g/m²), then convert to kg/s.

Worked example A (paper web, aqueous ink)

Width: 1.6 m; speed: 30 m/min = 0.5 m/s

Water removal: 5 g/m²

Area per second: 1.6 × 0.5 = 0.8 m²/s

Water mass: 0.8 × 5 g = 4 g/s = 0.004 kg/s

Phase change: 0.004 × 2,256.7 kJ/kg = ≈ 9.0 kW

Overhead (≈ 30%): ≈ 12 kW installed across zones

Worked example B (film substrate, thicker laydown)

Width: 1.2 m; speed: 20 m/min = 0.333 m/s

Water removal: 8 g/m²

Area per second: 1.2 × 0.333 ≈ 0.4 m²/s

Water mass: 0.4 × 8 g = 3.2 g/s = 0.0032 kg/s

Phase change: 0.0032 × 2,256.7 kJ/kg = ≈ 7.2 kW

Overhead (≈ 35% for gentler ramping): ≈ 9.7 kW installed, finer zoning recommended

Worked example C (high-speed narrow web)

Width: 0.5 m; speed: 80 m/min = 1.333 m/s

Water removal: 3 g/m²

Area per second: 0.5 × 1.333 = 0.6665 m²/s

Water mass: 0.6665 × 3 g = 1.9995 g/s = 0.002 kg/s

Phase change: 0.002 × 2,256.7 kJ/kg = ≈ 4.51 kW

Overhead (≈ 25% with strong airflow): ≈ 5.6 kW installed; high response emitters help with frequent cycling

Quick answer — “How do I estimate power fast?”

Multiply area-per-second by g/m² to get g/s, convert to kg/s, multiply by 2,256.7 kJ/kg, then add 20–35% overhead. Validate with trials.

IR raises surface temperature, but vapor must be carried away to maintain gradients that drive mass transfer.

Design practices

Directed airflow: Use air knives or slot nozzles to break the boundary layer and transport vapor away from the surface.

Exhaust path: Provide a low-impedance path out of the dryer zone; avoid recirculating saturated air onto the web.

Staging: Start with lower irradiance to avoid skinning, increase mid-zone to accelerate bulk removal, then taper for surface finish control.

Shielding and reflectors: Keep reflectors clean; ensure guards do not shadow critical regions.

Common pitfalls and fixes

Micro-blisters: Reduce initial peak irradiance, increase airflow, verify coat weight uniformity.

Re-condensation or “dull” finish: Increase exhaust, slightly raise final-zone temperature, check exit web temperature before contact points.

Control layers

Zonal control: Divide emitters across width and length; tune edges independently to correct profile droop or overshoot.

Temperature feedback: Non-contact pyrometers aimed at the inked surface give fast response; compensate for emissivity and reflections.

Moisture or mass-loss indicators: Use inline sensors where available or implement weigh-and-bake offline checks to calibrate.

Supervisory logic: Ramp-rate limits, anti-windup in PID loops, and recipes by substrate/coverage range.

Sensor placement tips

Aim at the surface that governs quality (usually the printed side).

Shield sensors from stray radiation; avoid specular glare.

Validate readings at representative speeds and coverages; keep a calibration log.

Quick answer — “How often should calibration be done?”

At minimum quarterly, and after emitter replacement or major process changes. Replace sensors that drift beyond tolerance.

Treat IR stations as industrial ovens or dryers and design accordingly.

Design and engineering

Provide positive ventilation sized for worst-case vapor loads.

Interlock doors and guards; define safe-state behavior on trips and power loss.

Include over-temperature protection in each zone and emergency-stop integration.

For solvent-bearing processes, apply appropriate monitoring and electrical classification where required.

Commissioning

Verify airflow rates and exhaust direction.

Map temperature uniformity across width at typical speeds.

Document startup, shutdown, jam recovery, and loss-of-air scenarios.

Operations and maintenance

Daily: check emitter status, reflectors, and alarms.

Weekly: clean reflectors, confirm sensor offsets, inspect wiring and shielding.

Quarterly: re-profile zones under worst-case coverage; review logs for drift and nuisance trips.

Quick answer — “What about solvent inks?”

Ventilation, interlocks, and, where applicable, vapor monitoring are mandatory. Commission and audit as you would any heated process that can see flammable atmospheres.

Drying affects dot gain, gloss, and adhesion. Faster is not automatically better if it causes nonuniform film formation.

Guidelines

Stabilize pre-heat: Keep substrate temperature entering the print zone within a narrow band; this reduces viscosity swings and banding.

Balance zones for finish: Moderate final-zone power to avoid gloss shift; let airflow do more of the last-stage work.

Measure and document: Track tone value increase, colorimetry, and gloss before and after changes. Tie dryer recipes to press color targets so operators cannot inadvertently shift appearance.

Quick answer — “Will faster drying affect color targets?”

It can. Use controlled pre-heat, staged power, and measurement routines to keep TVI and color within tolerance.

Cockling or wrinkling (paper)

Causes: excessive peak power, uneven edge-to-center profile, moisture imbalance.

Fixes: trim edge zones, raise distance, add gentle pre-heat for moisture equilibrium.

Pinholes or micro-blisters

Causes: skinning before bulk solvent or water escapes; inadequate airflow.

Fixes: reduce initial irradiance, add directed airflow, verify coat weight and ink rheology.

Blocking or set-off

Causes: insufficient surface set before winding or stacking.

Fixes: increase final-zone dwell, add brief cooling/air assist before contact, confirm exit web temperature.

Gloss mottle or shift

Causes: nonuniform heating, temperature overshoot.

Fixes: tighten PID, improve sensor alignment, flatten profile via zonal tuning.

Banding or color drift

Causes: thermal cycling affecting viscosity or dot formation.

Fixes: stabilize pre-heat, prefer fast-response emitters, confirm process control targets.

Substrate warping or yellowing (films/textiles)

Causes: overheating or spectral mismatch.

Fixes: move toward medium/longer wavelengths, lower power density, re-profile zones before closing distance.

IR systems are reliable when kept clean and operated within design limits.

Best practices

Keep reflectors and guards clean; dust reduces efficiency and causes hot spots.

Avoid fingerprints and contamination on quartz components; handle with gloves.

Limit unnecessary high-power cycling; use soft-start and ramp-down recipes.

Maintain spare emitters and critical sensors; record hours and swap proactively.

Quick answer — “What maintenance extends emitter life most?”

Clean optics and reflectors regularly, control dust, and minimize harsh on-off cycling with sensible ramp profiles.

Phase 1 — Define and measure

List the job mix: inks, substrates, speeds, coverage ranges, allowable temperatures.

Measure baseline exit web temperature, moisture, and defects at current speed.

Estimate volatile mass flow for each representative job.

Phase 2 — Specify and prototype

Choose emitter family based on absorber and substrate sensitivity.

Size installed power using the baseline formula and examples; plan zones.

Define airflow and exhaust; aim for strong boundary-layer disruption without disturbing registration.

Instrument with pyrometers and, where possible, moisture or mass-loss checks.

Phase 3 — Commission and lock in

Ramp test at low coverage; record temperature and defects.

Introduce worst-case coverage; re-profile zones and airflow.

Document recipes per substrate and coverage band.

Train operators on alarms, interlocks, and upset procedures.

Phase 4 — Optimize and maintain

Review logs weekly for drift or nuisance trips.

Audit color and finish monthly to confirm stability.

Re-calibrate sensors quarterly; refresh SOPs after any equipment change.

Power density (kW/m²): Radiant power at the web plane.

Emissivity: Efficiency term affecting how surfaces emit and absorb IR; influences pyrometer readings.

Dwell time: Exposure time under effective irradiance.

Boundary layer: Thin air layer at the surface that resists mass transfer.

Zonal control: Independently adjustable emitter sections across width and length.

TVI (tone value increase): Dot gain metric used to manage color consistency.

Match emitter spectrum to absorber and substrate limits.

Size from volatile mass flow; add 20–35% overhead; confirm with trials.

Use zonal control, staged power, and strong boundary-layer disruption.

Aim sensors at the governing surface; calibrate routinely.

Engineer ventilation, interlocks, and safe-state logic for upset conditions.

Tie dryer recipes to color and finish targets; document and train.

Keep optics clean, handle quartz with care, and limit harsh cycling.

One-sentence overview: Infrared heating, correctly specified and instrumented, lets digital printing lines run faster while protecting color, finish, and substrates; this guide explains the physics, selection, sizing, control, safety, troubleshooting, and rollout.

— Last modified: 2025-11-12